On Friday, March 22, five CHEPS students attended the 2024 Disability Visibility Symposium put on by U-M Mechanical Engineering and U-M Computer Science and Engineering. There, lightning talks from Mechanical Engineering, Computer Science and Engineering, CAEN, and Robotics representatives addressed the topic of disability and accessibility within engineering education.

Content at the Disability Visibility Symposium closely aligned with CHEPS’s mission to utilize engineering to improve healthcare, a societal pillar essential for all—especially those with disabilities. Symposium speakers shared the work that U-M has been doing to create a more accessible campus through a new “Quiet Room” in the Bob and Betty Beyster Building, modified shop equipment in Mechanical Engineering classes, and increased awareness around the prevalence of ableism.

From the talks, Industrial and Operations Engineering (IOE) sophomore Cole Martin took away three main points:

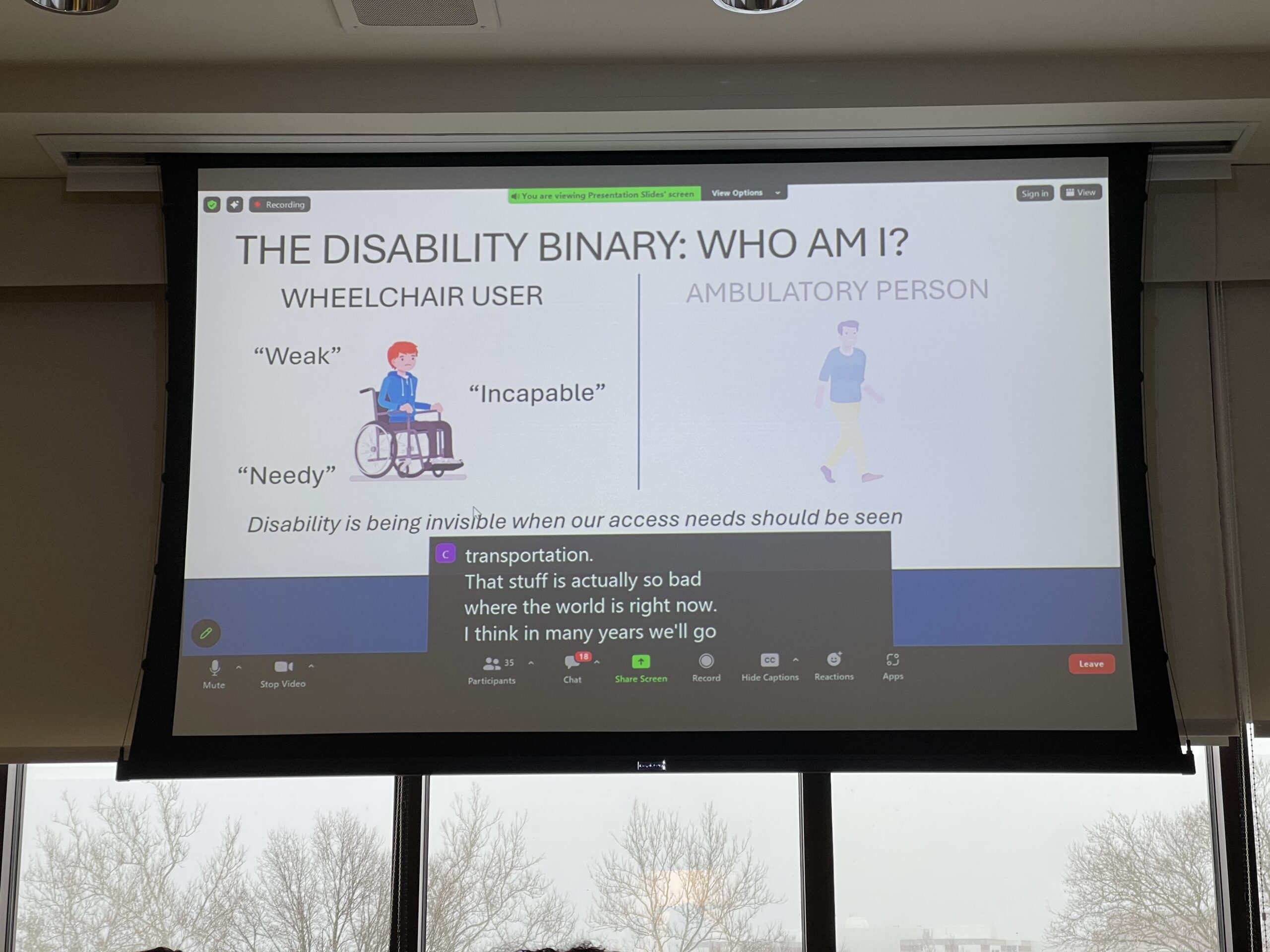

- Disability is not a binary, but rather a wide-ranging spectrum.

- Disability can be viewed through many different lenses, e.g. medical and social.

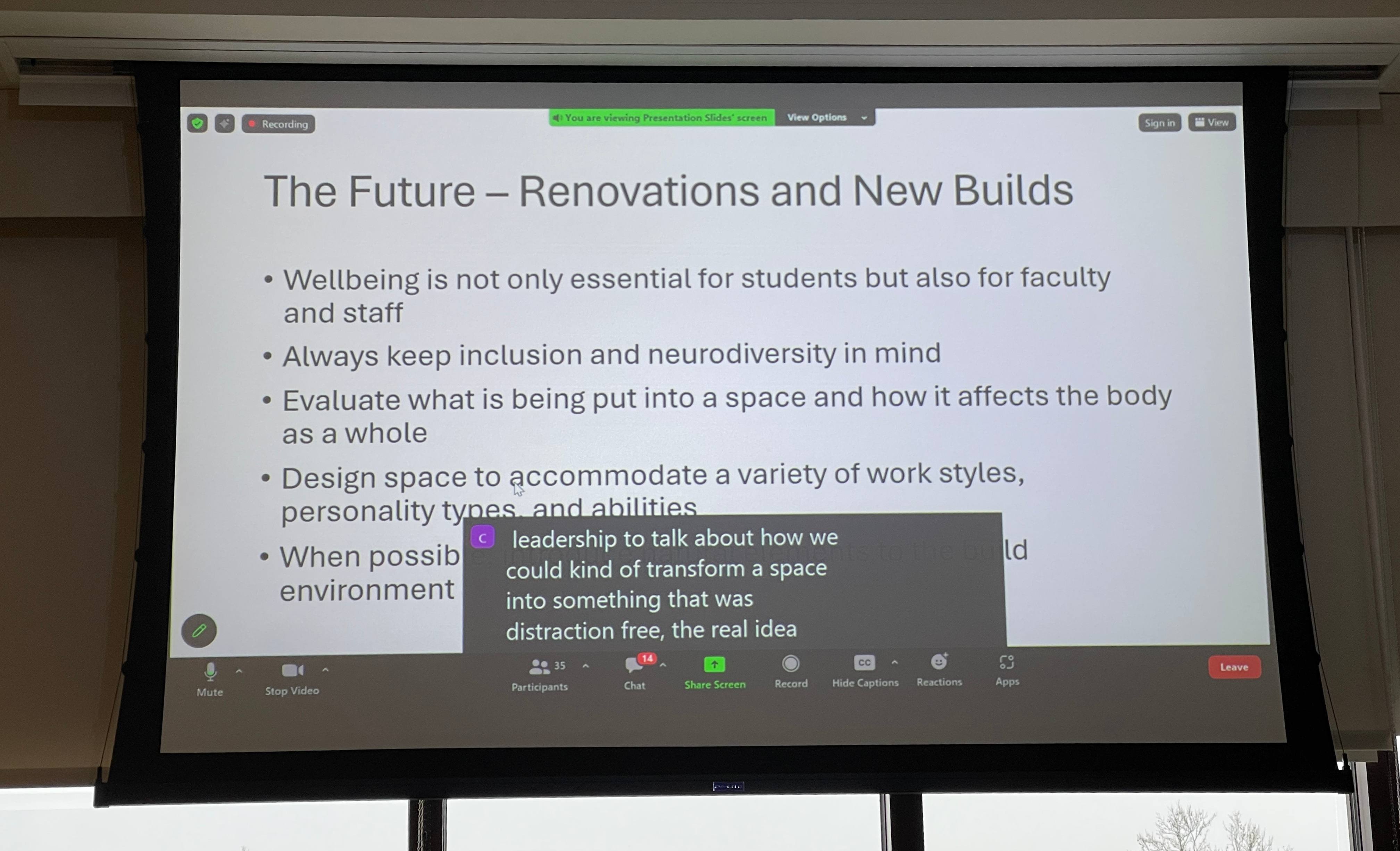

- Designing spaces to be accessible requires a little extra thought but not much extra work.

Not a binary, but a spectrum

Like Cole, Computer Science and Engineering undergraduate Ethan Kraus was also interested in the prevalence of invisible disabilities.

“As a society, I feel as though we tend to have a predetermined view of what a ‘true disability’ is. But in reality, disabilities exist on a spectrum and we may not be aware of what everyone else is going through,” Ethan shared.

While accommodations—making changes to products, environments, and processes in order to respond to the known needs of others—requires self-disclosure of one’s disability status, accessibility does not. Instead, accessibility hinges upon the consistent prioritization of universal design in order to create things that can be used by all (e.g. adding subtitles to videos, installing automatic doors, enforcing a fragrance-free policy in the workplace) without having to be asked to do so. An accessible world is one in which everyone can thrive from the start. When we understand that disability has no single “look,” the importance of accessibility grows even clearer.

The different lenses of disability

Cole shared that he enjoyed learning about how “for many people with disabilities, their disability is such a core part of their identity that it’s offensive when engineers try to design solutions to ‘fix’ them.” This assumption that folks with disabilities need fixing is deeply harmful and rooted in ableism. In truth, disability is natural, as is all human variance.

While the medical model views disability as an individual’s pathological defect, the social model of disability asserts that it is ableist culture and inaccessible infrastructure that actively disable folks—not their own bodies or minds.

Disabled is not a dirty word, and (perhaps well-meaning) euphemisms like handicapped, handicapable, special needs, and differently-abled fail to tell the truth of the matter: that our society is to blame for placing barriers in the paths of folks with disabilities.

Designing accessible spaces

It is up to us to fix the environments in which we live and not attempt, in vain, to “fix” each other.

Hannah Eller, a junior studying Biomedical Engineering, reflected that problem solvers “should sit back and ask [themselves] if disabled folks really asked for what [they] are creating.”

One poignant example provided at the symposium was about building ramps and elevators instead of jumping right to inventing wheelchairs that can climb stairs, which many individuals with disabilities agree are unnecessary and generally unhelpful.

Hannah continued, saying, “Accommodating for disabilities can come in many different forms; we don’t always have to create novel inventions that change the ways of life for those with disabilities. Rather, we can make improvements to existing processes and products that do not inherently change the ways people are currently living their lives.”

And of course, not everyone wants to change. Many simply want a spot at the table.

“My main takeaway was how crucial disability visibility is in engineering spaces and how often it gets overlooked,” shared Gabe Ferriero, a junior studying IOE. “If the workspaces and lab equipment are not designed for all users, then you will never get the diversity and variety of backgrounds that are so essential to a collaborative workspace.”

Gabe was inspired by a lightning talk about U-M Mechanical Engineering’s recent project to increase the reach and maneuverability of their shop equipment after a student who uses a wheelchair enrolled in class.

Advice for other engineers

When asked what they would tell engineers who aren’t sure why thinking and talking about disability is important, students had a variety of answers:

“Look for ways that a product or service may not be suitable for people with different needs. Though such limitations may be subtle or difficult to spot, to the user who may otherwise be closed off from using this product or service, it could make a world of difference!”

Alexios Avrassoglou, IOE Graduate Student

“In order to make accessible products, you need a diverse team facilitating these conversations and contributing their experiences and perspectives. It is extremely important work and should be a major consideration in all work fields. Accessibility is not optional!”

Gabe Ferriero, IOE Undergraduate Student

“The whole point of our jobs as engineers is to make/improve upon things/processes that ultimately make people’s lives easier in some way. Why wouldn’t we encourage thinking and talking about disability in work and school spaces?”

Hannah Eller, BME Undergraduate Student

Food for thought

“As a CHEPS student, the Disability Visibility symposium was so influential to me because it reminded me that all engineering solutions should be able to accommodate disabled people,” shared Ethan. “After the symposium, I was able to reflect on the current projects I am working on to see if there are any aspects I can revise to make them more inclusive of individuals with disabilities.

“Everyone in the world might not keep disability in mind when creating a product, but why does that mean I have to do the same? Why can’t we as engineers at U-M make a conscientious effort to include the opinions of disabled individuals about our engineering solutions? Doing so will only help more people in the end.”

CHEPS extends congratulations and gratitude to U-M Mechanical Engineering, U-M Computer Science and Engineering, the symposium speakers, and all sponsors of this great event!

— Written by Hannah Buck, CHEPS Staff