Yueyun Xia, an Industrial and Operations Engineering student at U-M, reflects on her summer at CHEPS.

Looking back at my time at CHEPS this past summer, all of the memories swirl in my head: my handwriting on the whiteboards for the optimization model, meetings with collaborators, lunch and learns…but there are a few special moments that I’ll cherish most of all.

Amy’s chocolate

Professor Amy Cohn is one of the biggest reasons I joined CHEPS. She (and the sense of community she helps create) is my everyday motivation for work. We are encouraged to share our knowledge, collaborate between project teams, and explore new things. It provides me with the chance to look at what other people are working on, sometimes even helping in areas I’m good at. Also, Amy often sends out emails saying “tell me something you learned,” and awards us with chocolate for anything fun we share with her.

It is from one of those emails that I started thinking about using optimization to solve Sudoku problems (trivial and unrelated to work as Sudoku may seem). Amy encouraged me to come up with a formulation—actually, two different ways of formulation—as an additional requirement for me being an IOE student. With help from CHEPS’ Software Manager, Hooman, and my peers, we developed a Python code template for all CHEPS students to have a taste of optimization formulation and to code and solve an optimization problem. Such extra projects create a great sense of fulfillment for me, and of course earn me another chocolate!

Marina’s “I approve”

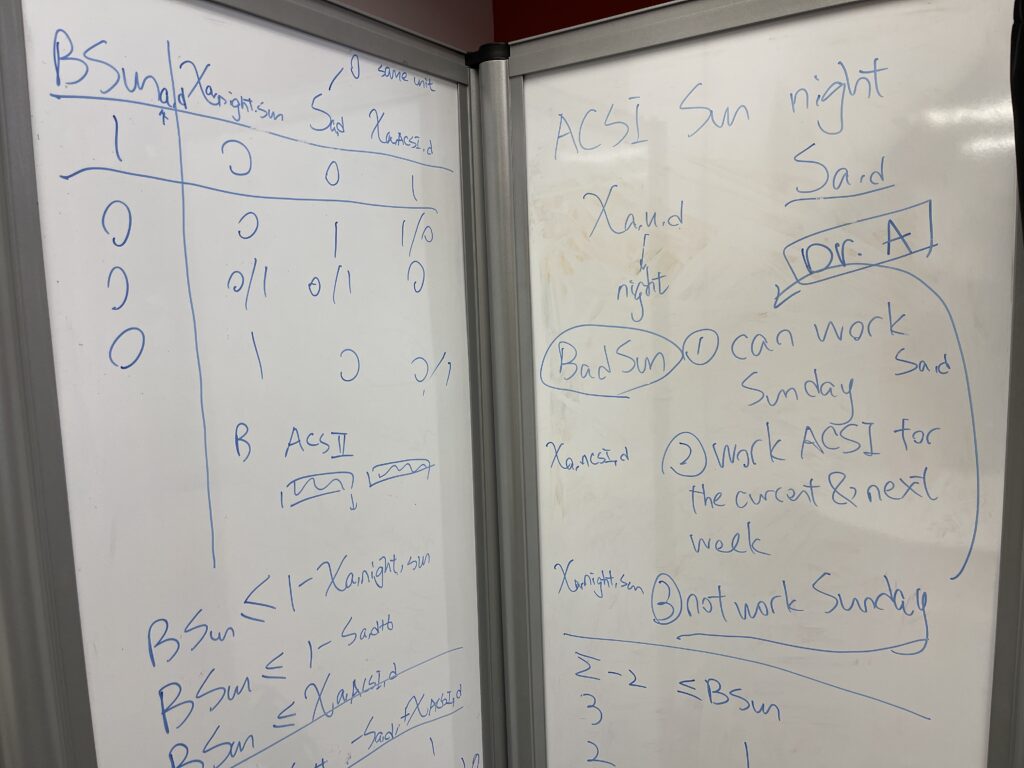

The work that first interested me in CHEPS was helping with staff scheduling in Michigan Medicine, as it was one of the typical examples Amy gave in her IOE 310 lecture. For me, it’s fascinating to see how we can translate word descriptions to mathematical expressions, and ultimately find optimal solutions to problems. Here, students can apply knowledge from the classroom to projects that are really making an impact. However, it is often challenging to turn brand new ideas to written equations. Over the summer, I’ve worked on formulating a staff scheduling model for the Acute Care Surgery division at Michigan Medicine.

We’ve talked about constraints and metrics; written down variables, constraints and metrics; and gone back and forth many times. By building the model block by block, I’ve realized how important it is to develop a top-down way of thinking. That is, what we write down today should ensure the flexibility to be generalized or otherwise changed in the future. Also, the mathematical notations (as well as the written descriptions) for constraints need to be carefully chosen and phrased so that it’s easy to follow for others who don’t necessarily have strong backgrounds in optimization or familiarity in this problem.

While we emphasize rigor, creativity is always encouraged as well. Once, when speaking to Professor Marina Epelman, I proposed a new way of formulating a constraint, which avoids introducing new variables and tricky linearization process. The excitement of seeing “I approve” in her email reply was worth all the head-scratching and writing… and erasing…and writing…and erasing…on whiteboards!

Premature baby model from visit to Clinical Simulation Center

Visiting the U-M Clinical Simulation Center was my first experience in a clinical setting. With my fellow CHEPSters, I toured simulated hospital rooms containing manikins of various sizes and ages. The manikins with miniature electric motors inside are so delicate that they’re able to respond to a provider’s action by demonstrating a change in pulse rate or oxygen level. Being a student with a mechanical engineering background, I could relate the design and control of such manikins to my studies.

Besides technical knowledge, there were also emotional touches to this tour. The pediatric room with a premature baby manikin inside reminded me of a professor’s personal story, and how he said that when someone is intubated, “It’s hard to imagine that some control engineers have to determine the volume of oxygen going into your loved ones’ lungs.” Healthcare can find people at their most vulnerable, and we may not always remember that when writing out math equations for staff scheduling or analyzing data on computers. Having the chance to step out of the office and be in a clinical environment reminded me of our work’s real impact on real lives.

— Written by Yueyun Xia, CHEPS Student