Participants:

Faculty/Clinicians/Staff: Alex Friedman Peahl, Amy Cohn

Students: Samir Agarwala, Claire Dawson, Dipra Debnath, Joshua Fink, Stephanie Ganzi, Leena Ghrayeb, Jordan Goodman, Suraj Harjani, Hannah Heberle-Rosse, Samuel Hocher, Shivani Jayendraprasad, Meghana Kandiraju, Luke Liu, Amanda Naccarato, Harini Pennathur, Nicholas Zacharek

Project Contact: [email protected]

Project Synopsis:

Prior to this work, prenatal care guidelines had remained unchanged in the United States for over a century, in spite of drastic changes in population health, patient preferences, and evidence of the impact of psychosocial factors on health outcomes and disparities. These guidelines recommended 12 to 14 in-person visits, regardless of patients’ medical or psychosocial risk factors. Tailoring prenatal care visit number and use of telemedicine to patients’ individual needs could provide higher value care, yet little was known about how these characteristics influenced actual prenatal care utilization.

In collaboration with Dr. Alex Peahl (OBGYN, Michigan Medicine), the team has worked to assess the prevalence of medical and psychosocial risk factors in a cohort of pregnant patients. In addition, the team has analyzed care utilization for patients with different risk factors. The long-term goal is to inform health system changes needed to support rightsized prenatal care: that is, care that matches patients’ needs to delivered services. By understanding what risk factors are most associated with poor prenatal outcomes, more patient specific prenatal care can be developed to better meet the needs of pregnant patients in the United States.

Tailored Prenatal Care

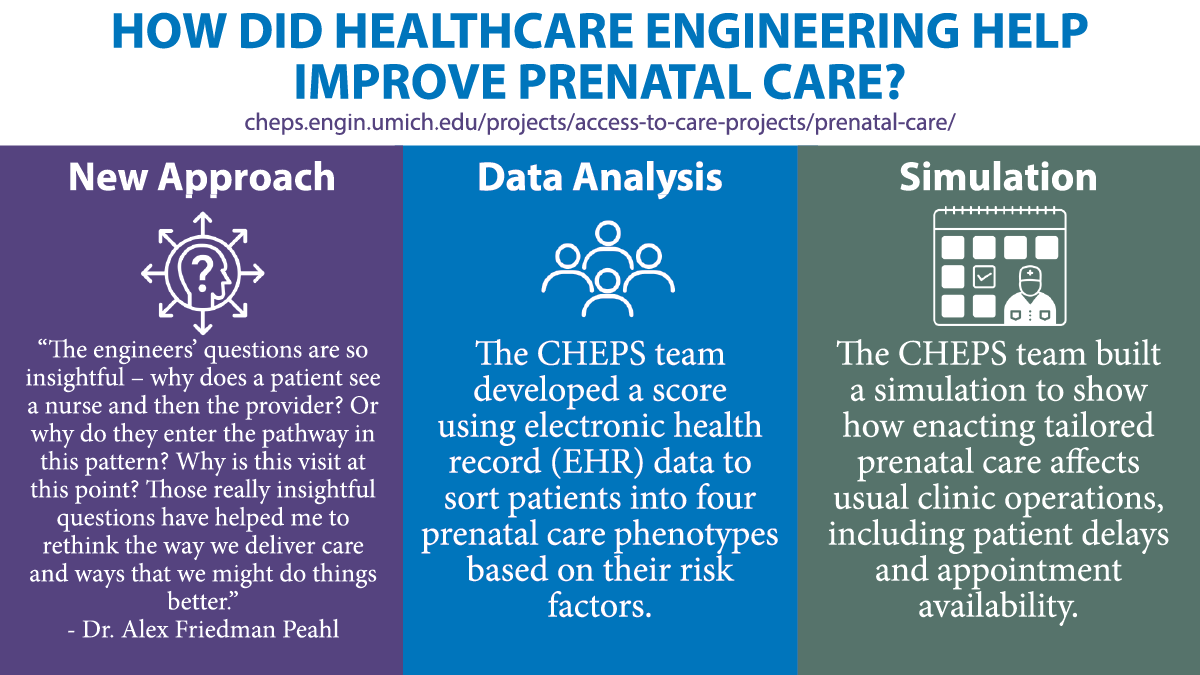

Since 1930, prenatal care guidelines in America have recommended a one-size-fits-all model with 12-14 in-person visits, regardless of individual patients’ psychosocial and medical risk factors. Recognizing that each patient has unique individual needs, CHEPS collaborator Dr. Alex Peahl worked with CHEPS students to understand how tailoring care would affect access to care. The team has developed a score using electronic health record (EHR) data to sort patients into four prenatal care phenotypes based on their risk factors. Now, they are analyzing data to understand how implementing tailored prenatal care schedules affects usual clinic operations, including patient delays and appointment availability.

Using Simulation to Test Prenatal Care Pathways

A successful plan needs to keep clinical operations running smoothly. The CHEPS Prenatal Team was able to help Dr. Peahl by building a simulation to show how enacting tailored prenatal care would affect clinic operations. The model simulates patient flow through the prenatal care system. Based on data analysis done at CHEPS, the team knew the probability of a patient being high-risk or low-risk so they were able to classify the simulation’s patients as they entered the system and designate which prenatal care pathway they would take. The CHEPS team then simulated an appointment, the scheduling of the next appointment, and so on, following the process through until the patient had completed their care. Some pathways are completely in-person while others incorporate some telehealth The model demonstrates how the new pathways and incorporation of virtual care impact the system operationally.

After running the simulation, the CHEPS team was able to measure factors such as how many patients were delayed and by how much as well as how often patients were overbooked due to capacity limits, or if any capacity went unused. Industrial and Operations Engineering Ph.D. student Leena Ghrayeb explained, “The idea is if we’re able to show that these new care pathways have similar or better outcomes than the current model, then we can justify adopting this new care model.” And the simulation did in fact show improvement in operations when these new prenatal pathways were implemented.

Providing Safe Care During the Pandemic

Dr. Peahl’s work proved invaluable when the COVID pandemic hit and Michigan issued a stay-at-home order starting March 20th, 2020. “We redesigned the entire prenatal care plan [for Michigan Medicine] almost overnight,” said Dr. Peahl. “We rapidly had to change how we were doing prenatal care. We used reduced in-person visit schedules and telemedicine to help keep patients safe. We were really well-positioned to implement those new models at Michigan Medicine because we had been thinking about how to redesign prenatal care since before the pandemic. A big part of that had been explored through the CHEPS work, which directly informed our care model during the pandemic.”

Making a Positive Difference

The change to prenatal care at Michigan Medicine has received good feedback from patients and providers. A recent survey of patients and providers showed high satisfaction scores and high perceived safety. Many patients and providers believe the new models provided improved access to care. Dr. Peahl said the survey also helped her see where the pathways could be improved. For example, it was crucial to have home devices, specifically a blood pressure cuff which is now a mainstay of any path with a virtual component.

“We also learned that the model wasn’t right for everyone. Patient choice is a crucial piece, outside of the acute pandemic when reduced viral exposure isn’t the only concern,” said Dr. Peahl. As an example, she noted a difference between patients in their first pregnancy not knowing what to expect and wanting more in-person guidance as opposed to patients in their second pregnancy or beyond who were much more comfortable with virtual care. Thinking about how to best support patients going through their first pregnancy is an important part of the model.

Bringing About Change Through Collaboration

Because of the work done at Michigan, the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists invited Dr. Peahl and her team to help revise their prenatal care guidelines. A panel codified a lot of the procedures that Michigan Medicine used during COVID. That plan, named “The Plan for Appropriate Tailored Care in Pregnancy” is now the national standard of prenatal care. This is the first update to recommended prenatal care guidelines in the United States since the 1930s.

In addition to being encouraged by the impact of this work on patients locally and through the nationwide adoption of tailored prenatal guidelines, members of this project found the collaboration rewarding. Leena appreciated the chance to bring her engineering skills to a project that could have such a positive effect on patients. She said, “I’m proud of it all. It’s such an important project because of the fact that it has such heavy implications. We know that there’s a disparity in terms of maternal mortality and things like that based on race and one of the reasons is that we’re not taking into consideration medical and social risk factors. So the fact that we get to be a part of this huge policy change is mind-blowing. And I’m very grateful and humbled to be a part of it.”

Likewise, Dr. Peahl said, “It is such a joy every time I work with CHEPS. Having an engineer’s perspective of medicine is so critical to thinking about delivering care in a different way. Often in medicine, we just continue doing what we’ve always done because of dogma or practice. The engineers’ questions are so insightful – why does a patient see a nurse and then the provider? Or why do they enter the pathway in this pattern? Why is this visit at this point? Those really insightful questions have helped me to rethink the way we deliver care and ways that we might do things better.”

Papers, Posters, & Presentations:

Posters:

- “Using Discrete-Event Simulation to Rightsize Prenatal Care.” Engineering Research Symposium, Ann Arbor, MI, February 2021.

Presentations:

- “Scheduling Prenatal Care Visits for Patients with Varying Medical and Social Risk Factors.” INFORMS Annual, Anaheim, CA, October 2021.